This is a free fortnightly newsletter about the New Zealand Net.

If you would like to be notified by email when a new edition is published, please contact ZL1NZ.

Browse our Newsletter Archive and List of Net Tips.

Featured key

This WT 8 Amp Nr 2 Mk III key holds special significance for its owner. Photo: VK1KVS

By Kees van der Spek VK1KVS

Between September 1973 and November 1975, I worked as a conscript CW operator in the Royal Dutch Army Signal Corps. I took a posting to Suriname, the former Dutch colony in South America until its independence on 25 November 1975.

The Morse key that permanently closed the daily ‘every-hour-on-the-hour’ telegraphy communications between army headquarters in the Netherlands and the Dutch Armed Forces in Suriname on 24 November 1975 became the first item in my collection of keys. Although ‘only’ a standard late-model Key WT 8 Amp, its provenance and unique historical context make it a prime possession in my collection.

* Read more about key collecting in the feature article by Kees later in this NZ Net News.

* If you have an interesting key for this feature, please send me a nice clear photo and a few words describing it.

Quick notes

On a recent trip south, Gerard ZL2GVA enjoyed a visit to the Voice of Swannanoa, Grant ZL2GD. The lads are pictured here, with GVA on the right.

On a recent trip south, Gerard ZL2GVA enjoyed a visit to the Voice of Swannanoa, Grant ZL2GD. The lads are pictured here, with GVA on the right.

The Oceania DX Contest – CW edition will start on Saturday 8 October at 0600Z and run for 24 hours.

Fancy a Pendograph key? These don’t come up for sale very often, but Herman VK2IXV has decided to sell one of his. If you’re keen, you can find his address on qrz.com. And if you’re not familiar with the Pendograph, I’ll post a video later in this newsletter.

If you are signed up for an email notification each time NZ Net News is published, you may not have been getting them consistently – or they may have been going to your spam folder. This is all due to the various and evolving types of spam filter that email providers use, and it’s hard to get around them. I have, however, installed a new system to send out the notifications, starting with this newsletter. I would be interested in hearing whether you did, or did not, receive the email – and how this compares with recent experience. Thanks for your understanding. Also, there are a few simple things you can do which may teach your email system that NZ Net News isn’t spam. And if you are still having problems, you can always find the latest edition on the archive page, which is updated around 1000 UTC every second Friday, just before the email goes out.)

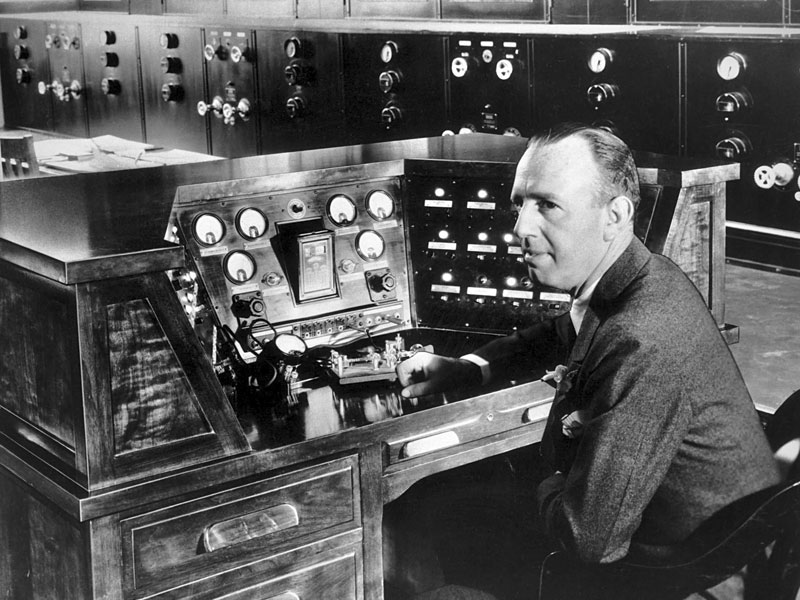

Photo flashback

27 April 1934, Cincinnati, Ohio: “Powel Crosley Jr, young radio magnate, is shown here at the control console of his new 500,000-watt transmitter, WLW, the largest broadcasting station ever built, which was dedicated recently. This operator’s control is in itself a brilliant achievement in radio engineering. Through it is provided complete control and supervision, not only for the WLW transmitter, but also for the Crosley WSAL and short-wave W8XAL transmitters.”

You will have noticed the Vibroplex Lightning bug on the desk, although I’m not sure what role it played at this station. I recall reading years ago that Crosley started out with a 5W broadcast transmitter, but quickly realised that to get a significant improvement in signal strength he would need a gain of 10dB, so he built a 50W transmitter. Then he just kept on going, with transmitters of 500, 5000 and 50,000 watts until he ended up with this 500kW beast. They say it really got out well. 🙂

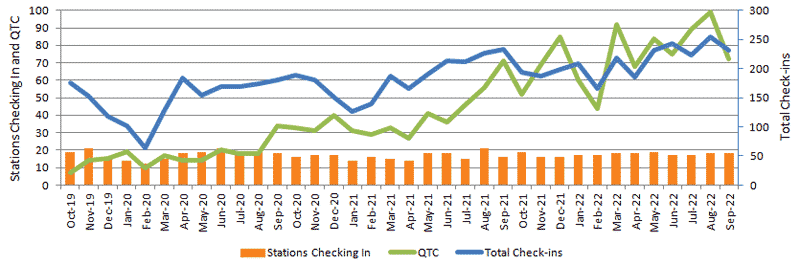

Net numbers

Here are the NZ Net numbers for September, sneaking in to the newsletter right on deadline, as I didn’t want to wait another two weeks to publish them.

NR40 R ZL1NZ 45/42 AUCKLAND 0813Z 30SEP22 = NZ NET = SEP QNI VK3DRQ 16 VK3GDM 1 VK4PN 13 ZL1AJY 2 ZL1ANY 16 ZL1BWG 20 ZL1NZ 20 ZL1PX 13 ZL1RA 10 ZL2GD 18 ZL2GVA 14 ZL2KE 16 ZL2LN 10 ZL2TE 11 ZL3TK 21 ZL4CU 3 ZL4FZ 2 ZL4KX 15 TOTAL 231 QTC 72 = ZL1NZ

Morse keys as a niche interest

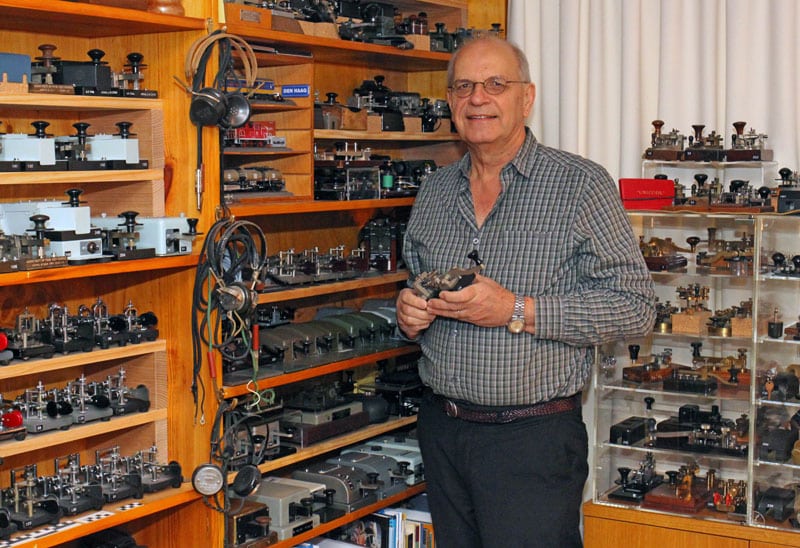

Kees VK1KVS with his morse key collection

By Kees van der Spek VK1KVS

In his preface to The Telegraph in America, James D Reid wrote in 1886: “with ever increasing power, the telegraph has become not only the master of commerce, but the tongue of mankind.”

From 1844 onwards, Morse code became a near universal language, erasing distances, and the ‘key’ that opened up the world. How fitting, then, that – apart from other terms used at one time or another (‘correspondent’, ‘manipulator’; ‘transmitter’) – the universal term in English (and several other languages) for the instrument that allowed Morse code to be articulated was to become ‘Morse key’ or ‘telegraph key.’

For both former professional telegraphists and today’s amateur radio CW operators, Morse keys encapsulate the history of communications and telegraphy in one small and often beautifully made artefact. For some, collecting Morse keys has become a particular stand-alone ‘niche’ interest, or an interest that is closely linked with their amateur radio activities. But especially for those who have professionally communicated in Morse, a continuing interest in telegraph keys is a more personal matter: for them the key was once their ‘tool of the trade,’ inseparable from the training that underpinned their professional qualifications and that enabled them to earn a living.

By worldwide agreement, commercial ship-to-shore radiotelegraphy ceased on 1 February 1999, with satellite communication becoming the norm. The occupation of ship’s Radio Officer, the last of the professional telegraphists, disappeared overnight. The use of radiotelegraphy by the military had mostly ceased during the mid-1970s. Seen in that light, Morse keys as used for radiotelegraphy – and its predecessors, the electric landline telegraph and undersea cable telegraph networks – have become artefacts of industrial archaeology, signposts of the material culture of a bygone civilian, commercial and military communications era.

If only they could speak

As industrial-archaeological artefacts, telegraph keys embody the history of particular occupations that have disappeared and the social, commercial, and military significance of Morse communication that made those occupations important. They still hold within them – if only they could speak – the connections with the electrical engineers, instrument makers and telegraphists who designed, manufactured, and worked with them.

The evolution of Morse keys and their production by manufacturers in many different countries have resulted in an endless variety of designs, forms, materials, and degrees of greater or lesser technical and engineering complexity. The stylistic variability of telegraph keys often allows them to be identified with specific use categories – postal, commerce, army, navy, air force, civil aviation, merchant navy, police and emergency services, amateur radio. Often we will know the names of their manufacturers by simply looking at them.

What may motivate a fascination with Morse keys is not just their stylistic variability and engineering excellence, but a desire to keep their history alive, as an ongoing reminder of the social and technological context within which Morse communications existed.

Morse keys remain as the visible remnants of an occupation and professional specialisation now entirely lost. As the repository of all those lost messages held within them – even if only inferred in the vaguest of terms – they are worthy of recognition, admiration and preservation.

QSL card is a work of art

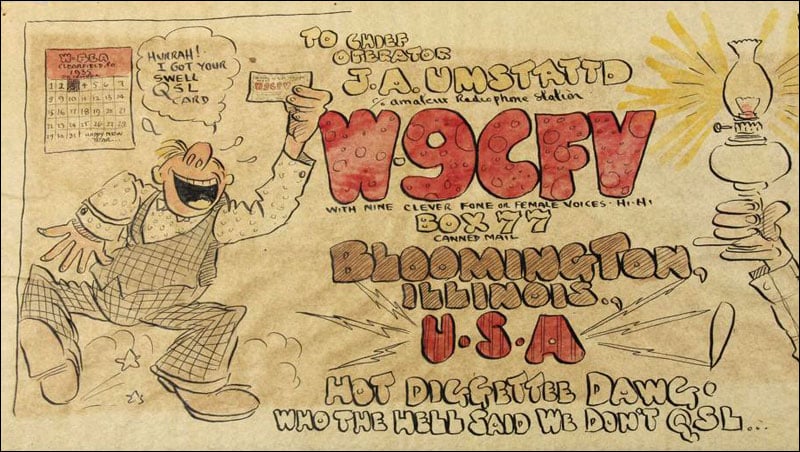

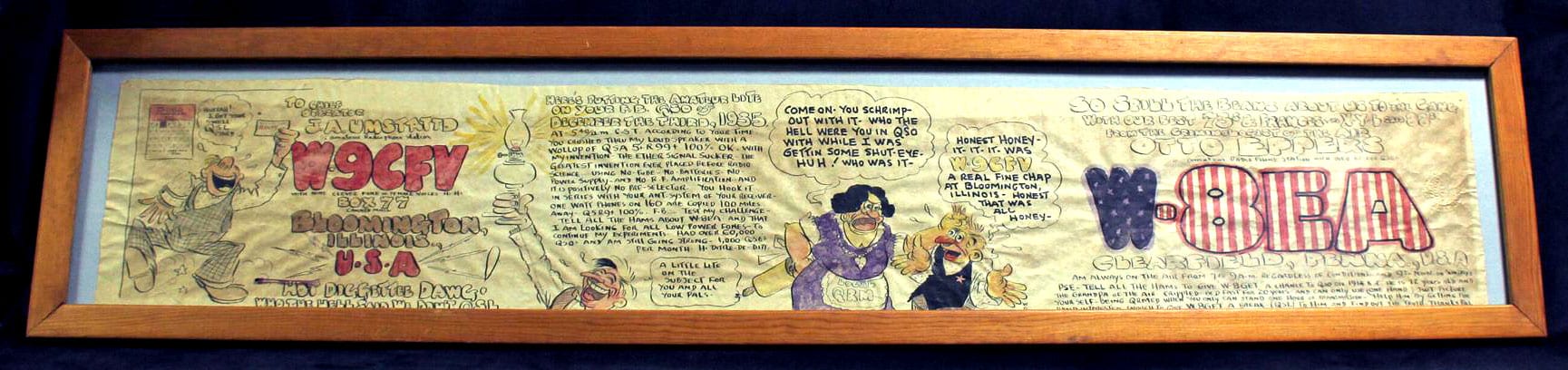

A small portion of a 1935 QSL card sent to W9CFV by W8EA

The photo above is just part of an enormous, highly personalised QSL card, hand-drawn and sent by Otto Eppers W8EA to James Umstattd W9CFV in 1935. Otto was a professional cartoonist, as you probably guessed, and this 87-year-old card is now in the collection of the McLean County Museum of History in Bloomington, Illinois.

Photos: McLean County Museum of History. Click to enlarge.

I recommend reading this entertaining newspaper article about the card. The overall dimensions are unknown, as those stated in the article (44×22 inches) appear inconsistent with the proportions of the card in the photo.

Numbered radiograms list grows

By James Wades WB8SIW

After a two month public comment period, the Radio Relay International (RRI) Emergency Communications Committee has released the final, approved version of the new RRC Numbered Radiogram Texts.

These texts are backwards compatible with the older ARL Numbered Radiogram Texts. However, this new list adds a variety of additional texts, some of which were developed to accommodate the needs of local EmComm organisations and served agencies, and some of which were designed to provide options that are suitable to emergency operations, and which were harmonized with the National Emergency Communications Response Guidelines in the USA (“National Response Plan”).

Traffic operators may now use these new RRC texts on-air in the same manner as the older ARL Numbered Radiogram Texts.

Morse challenge

Here’s another recording of two stations agreeing to do something. The stations are two ships in New Zealand waters, probably about 30 years ago.

Your challenge is to identify the two stations by callsign and ship’s name. Then tell me what did they agree to do? You’ll need to infer a bit, as these ops didn’t waste any time chatting. 🙂

Please send your answers by radiogram, or by email if no propagation.

Answer to previous edition’s Morse Challenge

In NZ Net News 89 I asked why the letter O, one of the most frequently occurring letters in English, has one of the longer Morse representations.

The answer is that, in their original code, Morse and Vail did try to make the most common letters the shortest. They defined O as two dots separated by an internal space, rather like the letter I, but with a longer gap in the middle.

A few people realised that Morse Code, with its internal spaces and three different lengths of dash, could be simplified, and so they set about developing improved versions. Drawing on these ideas, the International Telegraphy Conference in 1865 adopted what we now know as International Morse Code.

The Morse code, as specified in the current international standard, International Morse Code Recommendation, ITU-R M.1677-1,[1] was derived from a much-improved proposal by Friedrich Gerke in 1848 that became known as the “Hamburg alphabet”.

Gerke changed many of the codepoints, in the process doing away with the different length dashes and different inter-element spaces of American Morse, leaving only two coding elements, the dot and the dash. Codes for German umlauted vowels and sch were introduced. Gerke’s code was adopted in Germany and Austria 1851.

This finally led to the International Morse code in 1865. The International Morse code adopted most of Gerke’s codepoints. The codes for O and P were taken from a code system developed by Steinheil. A new codepoint was added for J since Gerke did not distinguish between I and J. Changes were also made to X, Y and Z. This left only four codepoints identical to the original Morse code, namely E, H, K and N, and the latter two had their dahs extended to full length.

I received correct answers from ZL1ANY and ZL2GVA.

Video: Pendograph bug

Advertising archive

QST, Jan 1970

The Tymeter 24-hour digital clock, from Pennwood Numechron Co, was ubiquitous in ham shacks of the 1970s, at least in places with 60Hz power. (Does anyone know if they made a 50Hz version?)

The clock’s appeal isn’t surprising, when you consider that we had to keep a written log of every transmission, even all those unanswered CQs and tests. A Tymeter made that job so much easier.

Looking back at a photo of my 1970 shack in Toronto confirms that the Tymeter clock was the only item I had purchased new! I loved it, including the reassuring little click as each minute ticked over. I kind of wish they still made them.

Rumour has it that some hams who wanted extreme accuracy would fit a normally-closed push-button switch in series with the AC line, so they could stop the seconds wheel at :00 and let it start precisely on the time signal from WWV. I just pulled the power plug and reinserted it! I recall that there was a fair bit of inertia in the motor, so split-second accuracy would have been hard to achieve.

The top-of-the line models also had a buzzer that sounded every 10 minutes to remind the operator to ID in accordance with the FCC rules. How annoying that must have been.

Got a memory of some old gear you’d like to share? Drop me a line.

Suggestions?

If you have suggestions on how to make the NZ Net better, or things you’d like to see covered in these updates, please contact ZL1NZ. You might even like to write something for the newsletter.

Thanks for reading, and I hope to hear you soon on the NZ Net!

—

Neil Sanderson ZL1NZ, Net Manager

New Zealand Net (NZ NET)

3535.0 kHz at 9pm NZT Mon-Fri