For some of us, telegraph keys are objects of beauty. Indeed, some of the rarer models are quite popular with collectors.

I have just a few keys (or, as I like to call them, “digital communication devices”) most of which I have actually used over the years in amateur radio.

A: Straight keys

These are the simplest means of sending Morse code. They are really just finely balanced switches to turn the radio transmitter on and off. But it’s impossible to send much faster than about 15 words a minute on a straight key without a lot of wrist strain. Yes, Repetitive Strain Injury or Occupational Overuse Syndrome existed long before the keyboard and mouse; the old telegraphers referred to it as “glass arm”.

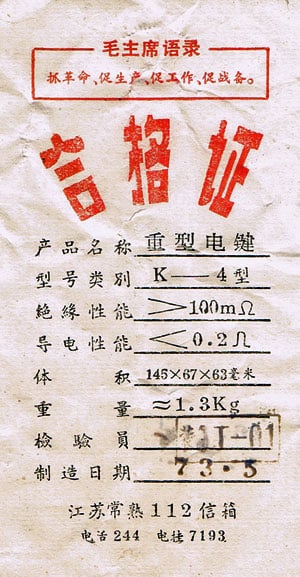

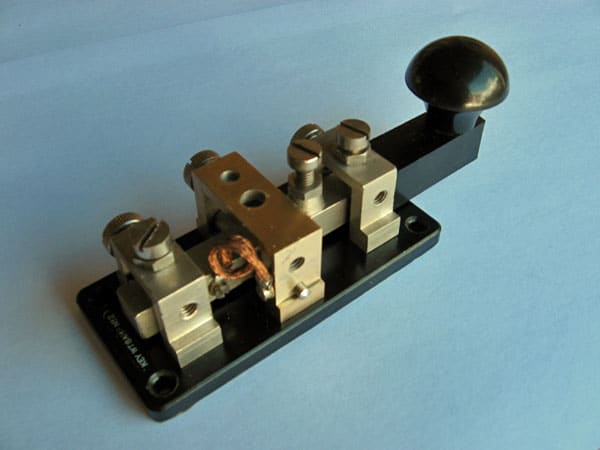

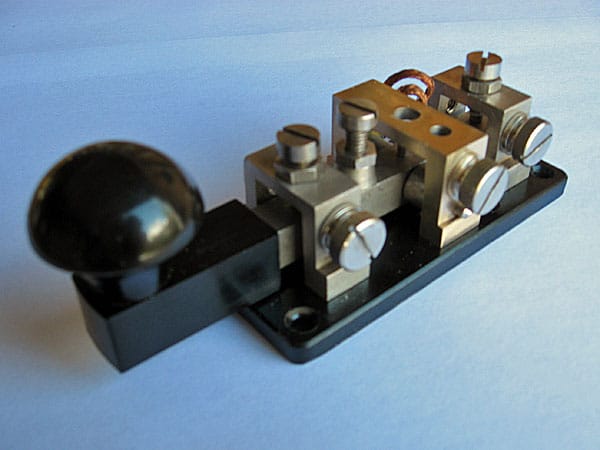

Chinese Peoples Liberation Army K-4 (D-117) key

This lovely key was a gift from Sichao BG5HSC who brought it from China for me in August 2016. It is quite heavy and has a very smooth action. I have it set up with extremely close spacing and it is a pleasure to use.

At right is the document that came with the key, showing it was made in 1973.

Marconi Marine 365FZ

A lovely, heavy key with ball-bearings. Repainting the cover is on the list of things to do.

Monarch key

Post Office or “GPO” key

This is an old double-contact key for landline telegraphy.

Signal Electric key

get in touch.

get in touch.

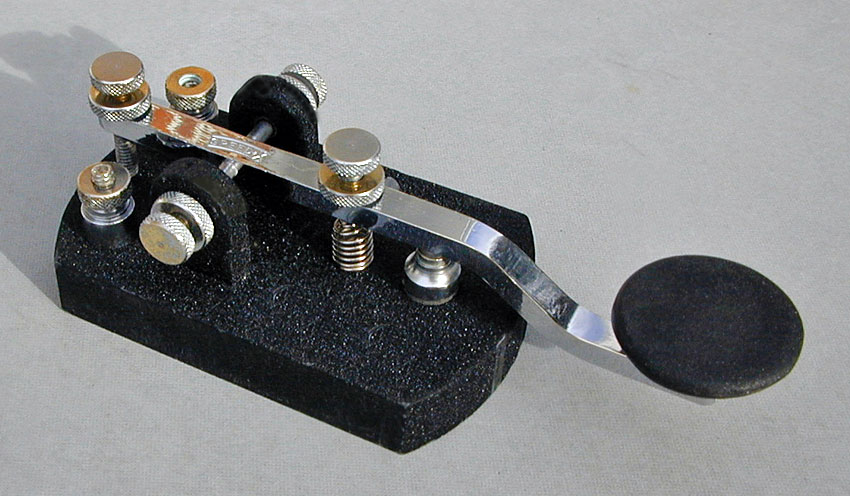

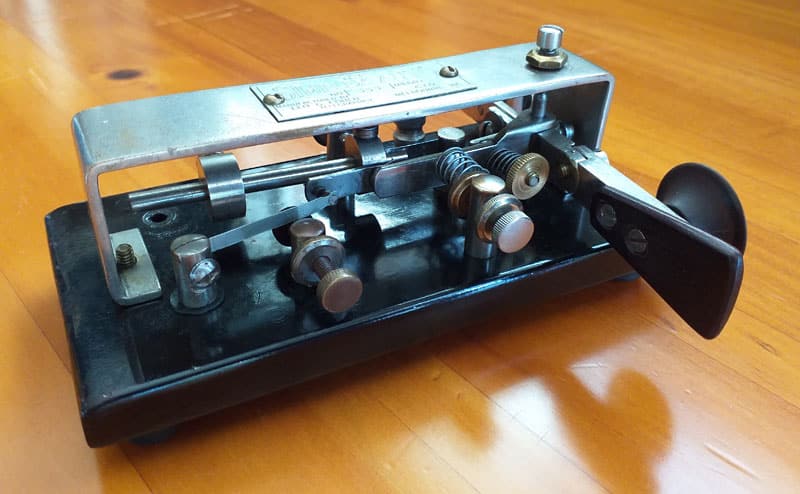

Speed-X 320 key (heavy) with removable cover

This was my first key, given to me by a veteran ham who worked with my father. I used it to learn the code for my licence exam, and then used it on the air until I moved up to a semi-automatic key. The Speed-X 320 keys were designed for radio work, and featured large (1/4 inch diameter) contacts.

This was my first key, given to me by a veteran ham who worked with my father. I used it to learn the code for my licence exam, and then used it on the air until I moved up to a semi-automatic key. The Speed-X 320 keys were designed for radio work, and featured large (1/4 inch diameter) contacts.

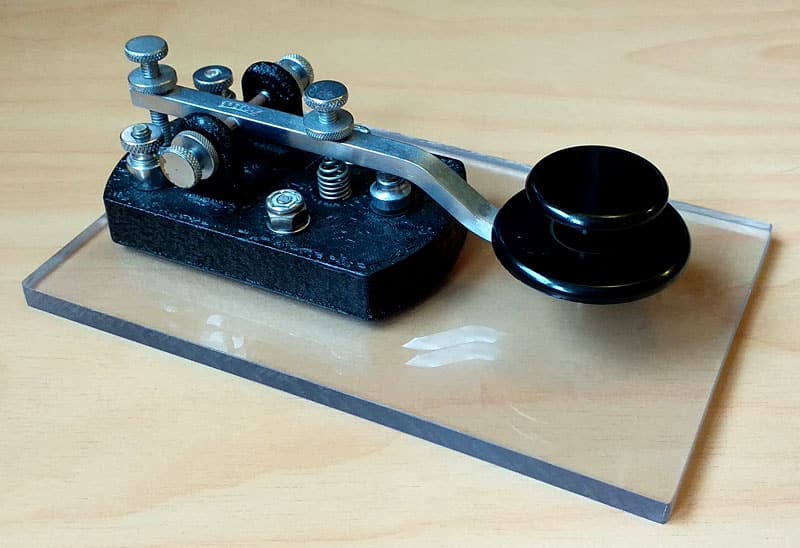

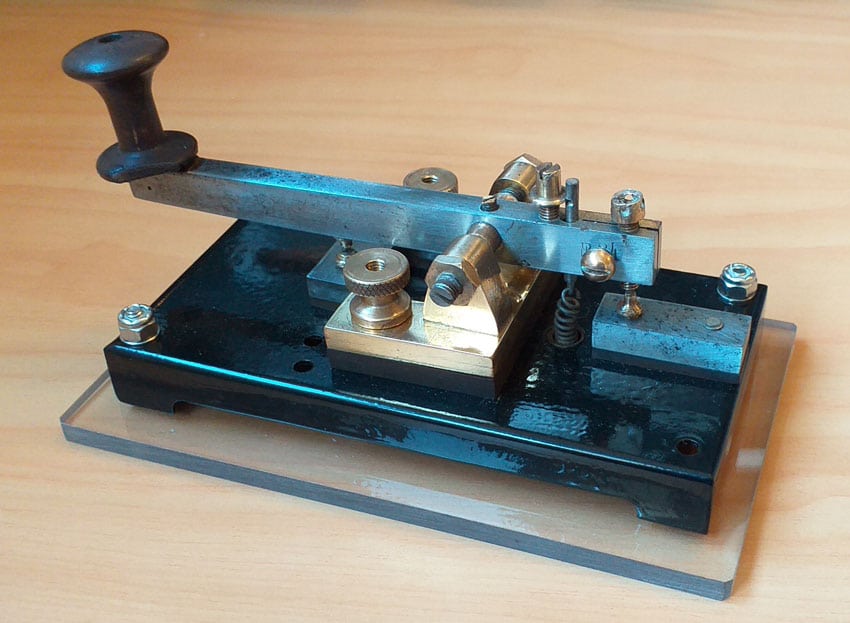

Speed-X 320 key (lightweight)

Although it has a much thinner and lighter base, this Speed-X key works just as well as the earlier version. It has the “Navy-style” double-decker knob which I prefer. Nickel-plated hardware. I have mounted it on 6mm thick clear acrylic.

World War 2 straight keys

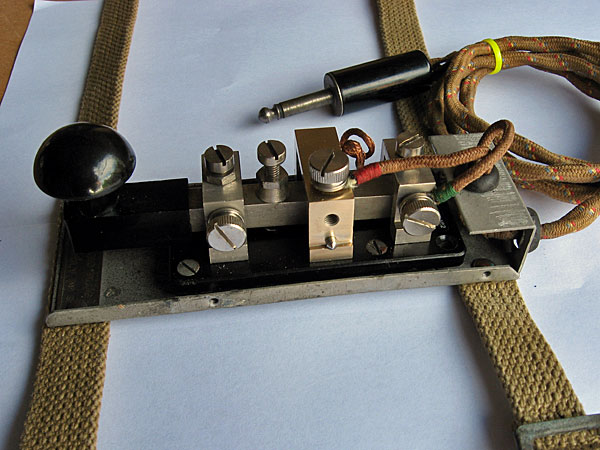

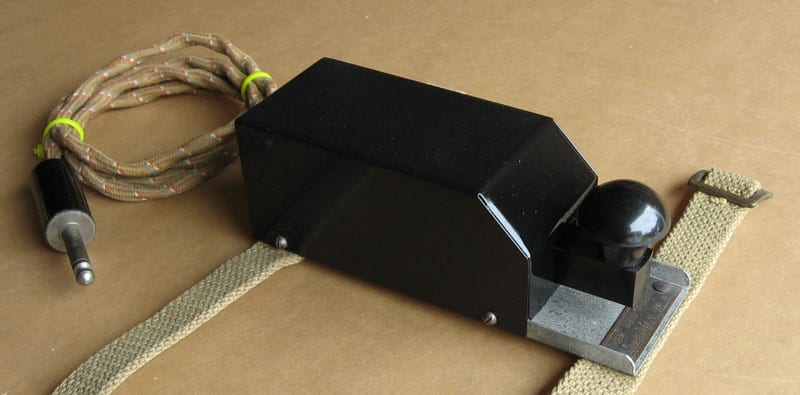

WT 8 Amp No. 2 key with leg mount (Key & Plug Assembly No. 9)

This double-contact key which can be wired from the left or right. This is an “upside-down key” in that the contacts are on the top of the lever.

- WT 8 Amp No. 2 military key in leg mount (Key and Plug Assembly No. 9)

- WT 8 Amp No. 2 military key

- WT 8 Amp No. 2 military key

- WT 8 Amp No. 2 military key

- WT 8 Amp No. 2 military key

- WT 8 Amp No. 2 military key

- WT 8 Amp No. 2 military key

- WT 8 Amp No. 2 military key in leg mount (Key and Plug Assembly No. 9)

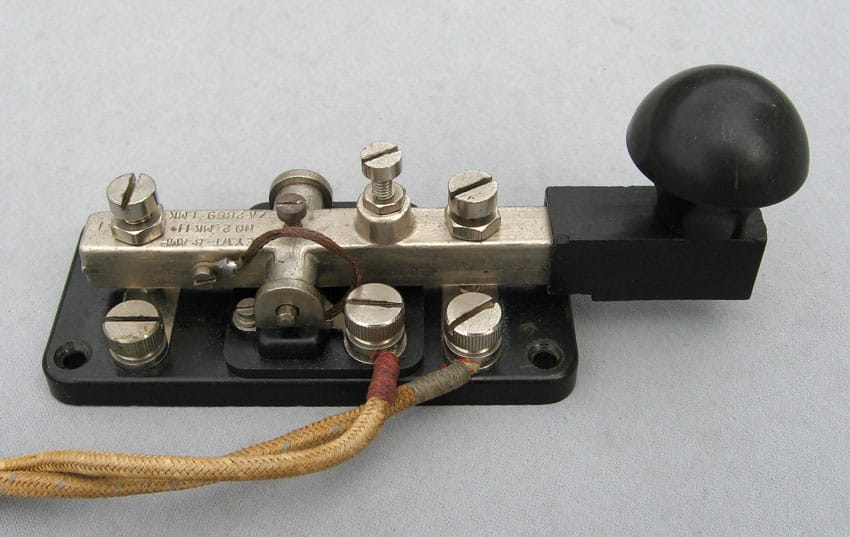

WT 8 Amp No. 2 Mk II key

This double-contact key which can be wired from the left or right.

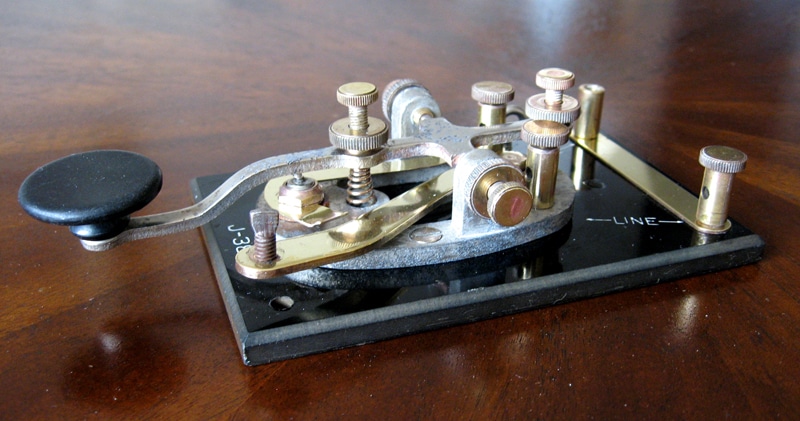

J-38 Signal Corps training key (USA)

The J-38 is the US Army Signal Corps designation for a J-30 key mounted on a black base with extra terminals to be wired up as part of a Morse training classroom during World War Two. They keys were made by various manufacturers, with subtle differences in construction.

My key was made by American Radio Hardware of New York City, and was owned by my friend’s father, Sam, VE7JU. J-38s became a favourite of radio hams who bought them as war surplus. After more than 40 years of disuse, my key was cleaned, polished and returned to the airwaves for Straight Key Night, 1 Jan 2011.

US Navy Flameproof key CTE-26003A

During World War 2, the US Navy copied the design of a German Luftwaffe key, and had it produced by various contractors. Many, such as this one, were made by Telephonics (hence “TE” in the part number).

The key’s contacts are fully enclosed to reduce the risk of an explosion when used near dangerous gases.

Some say that the key was intended for use with signalling lamps, although it was known to be a favourite of wireless operators.

Wigram key

The base, lever and some other parts are steel, while the trunnion assembly is brass. Such keys were made by trainees in the E&W School at Wigram Air Base in Christchurch during World War 2.

B: Semi-automatic keys (“bugs”)

When the lever is pushed to the right, these keys make dots continuously using a horizontal pendulum (the speed is adjusted by moving the weight(s) along the pendulum). This means faster sending and less wrist motion than with a straight key. Dashes are still made one-by-one, however, by pushing the lever to the left. They have lots of adjustments and need to be precisely set up to suit the individual operator and the desired speed.

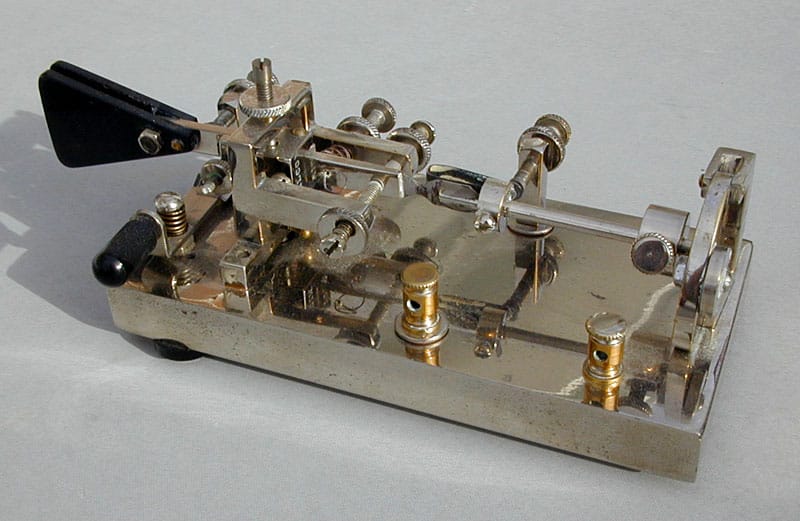

Dentsuseiki BK-50 ‘Swallow’ (1953-1968)

The BK-50 was made in Japan by Takaitsu Takatsuka. He later changed his company’s name to Hi-Mound and produced another well-known bug, the BK-100 which had a clear plastic cover and which became known as “the coffin bug.”

The BK-50 is fairly light, at just 1098g. When well secured to the desk it has a very easy feel, requiring less energy than many other semi-automatic keys.

Mac Key (1936)

A very heavy key, it can be turned on its side to use as a straight key too. Its designer, American Ted McElroy, was a world champion telegrapher, who received a phenomenal 75.2 words per minute in 1939, which he transcribed on a typewriter. This key looks clunky but is actually very smooth and easy to use.

Simplex Auto (c1930)

One of my oldest bugs is this lovely Simplex Auto from Melbourne, Australia. These bugs were made by Leopold (Leo) Cohen, a post office telgraphist. Mine is a 4th generation model, built between 1926 and 1932, and has serial number 664. Simplex Auto bugs are “right-angle” designs (compare with the other bugs shown below) but they also operate on the tension-release principle. In such designs, energy is stored in the pendulum which makes the dots. Pushing the dot lever releases the pendulum, allowing it to vibrate. (In the more conventional design, pushing the dot lever puts energy into the pendulum.)

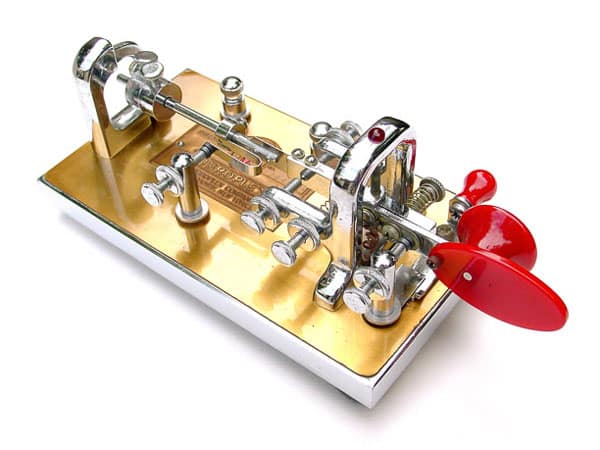

Vibroplex Presentation (1960)

This top-of-the-line Vibroplex has a 24k brushed gold-plated brass plate on a polished chrome base with bright chrome top parts. Like the Vibroplex Deluxe keys, it has jeweled movements. In addition to the two adjustable weights, this Presentation has an adjustable mainspring, something that was discontinued in later production.

Wilcox bug (1920s or 1930s)

Learn more about Wilcox keys, which were made in my hometown, Toronto.

C: Keyer paddles

These “keys” are really just very sensitive switches which connect to an electronic “keyer”. Pushing the lever to the right causes the keyer to generate an infinite string of dots, and pushing the lever to the left similarly generates dashes. The keyer uses electronic logic to ensure that the dots and dashes are perfectly timed and spaced, enabling high speed sending with very little hand motion.

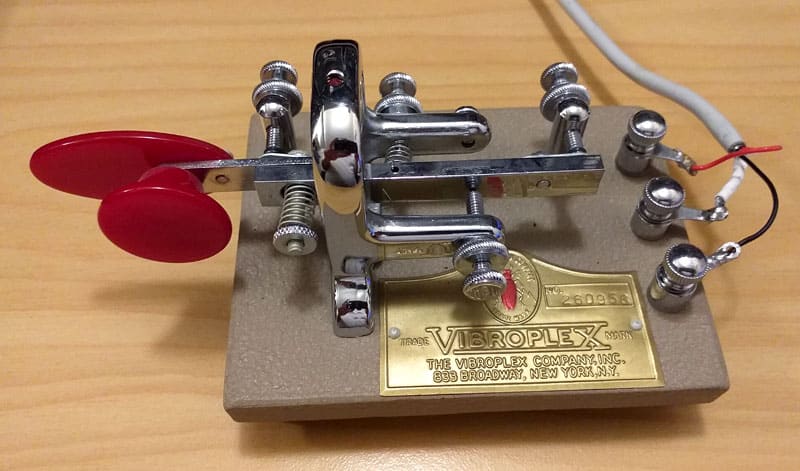

Vibro Keyer (USA)

Vibro Keyers were introduced in 1960, as the first commercially made paddles for amateur radio. Clearly adapted from the Vibroplex Original/Presentation bugs (see above) they are still being made, but are now known as Vibrokeyers (one word). All of the early Vibro Keyers, even those with the less expensive painted bases, came with jewelled movements and red finger pieces. Later, Vibroplex introduced a cheaper keyer with trunion bearings and black finger pieces.

The Deluxe model Vibro Keyer shown above was made in 1967. It has a chromed base, but is otherwise identical to the Vibro Keyer with painted base shown below.

The 1969 model shown above is the key I use every day. Like all Standard models, it has a painted base, in this case “sand” colour. Vibro Keyers were available in various colours over the years, including grey.

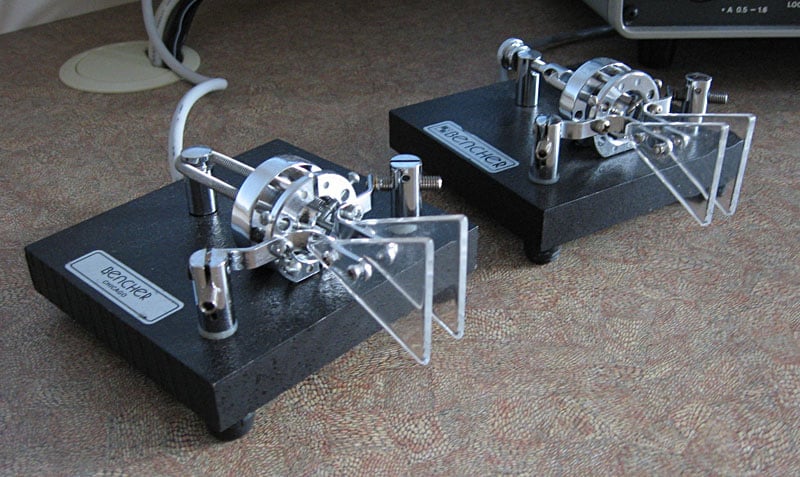

Bencher BY-1 dual-lever paddles and ST-1 single lever paddle (USA)

If you look closely, you’ll spot the differences between these similar paddles. The one on the right is a single-lever paddle, in which the dot and dash paddles move together – to the left (dashes), centre (off) or right (dots). On the left is an iambic (or “squeeze”) keyer in which the paddles move independently. If both paddles are pressed (“squeezed”) at the same time, the electronic keyer makes alternating dots and dashes, starting with whichever paddle makes contact first. This is perfect for letters such as “c” ( _ . _ . ).