This is a fortnightly newsletter about the New Zealand Net.

If you would like to be notified by email message when a new edition is published, please contact ZL1NZ.

You are also welcome to browse our newsletter archive.

Highlights

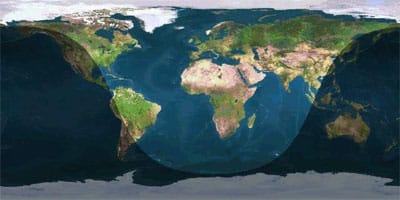

With these long nights and low temperatures, I hope you’ve been keeping warm with your radios, and enjoying some time on the lower bands. Propagation within New Zealand on 80m this past week has been up and down (pardon the pun) but trans-Tasman signals seem pretty good after 1000Z. There’s more on propagation coming up later in this newsletter.

With these long nights and low temperatures, I hope you’ve been keeping warm with your radios, and enjoying some time on the lower bands. Propagation within New Zealand on 80m this past week has been up and down (pardon the pun) but trans-Tasman signals seem pretty good after 1000Z. There’s more on propagation coming up later in this newsletter.

Here’s our net report for May. Thanks to everyone who checked in.

NR39 R ZL1NZ 47/44 AUCKLAND 0900Z 1JUN20 = NZ NET = MAY QNI ZL1AYN 2 ZL1BWG 9 ZL1NZ 21 ZL2GD 15 ZL2KE 5 ZL2LN 8 ZL2WT 19 ZL3AA 4 ZL3DMC 2 ZL3RX 2 ZL4CU 7 ZL4FZ 9 ZL4KX 8 ZL4LDY 15 VK2MZ 2 VK3DRQ 20 VK4AAT 1 VK4PN 4 VK7LDH 1 TOTAL 154 QTC 14 = ZL1NZ

Propagation, NZ Net and Local Contests

Ever wonder why some stations are hard to copy on the Net, even if not far away? Richard ZL4FZ has looked at propagation during this year’s Jock White Field Day, as well as on the NZ Net, and lays it out very clearly in the following article for NZ Net News. He also provides links to some great online resources.

In recent local contests, such as the Jock White Field Day, 40m propagation became very interesting. At the start of the contest on the Saturday afternoon, contacts to the upper North Island from Christchurch were reasonably easy to achieve with good signal strengths, but contacts to the lower North Island and Upper South Island were more difficult. Local contacts on 40m were almost impossible to achieve.

A look at the parameter known as f0f2 explains why this occurred. F0f2 is the highest frequency that can be reflected back from the ionosphere when a signal is transmitted directly upwards at 90°. At the date this was written (June 2020), the mid-afternoon f0f2 figure in Canterbury is often between 4 and 5 MHz.

What this tells us is that any signal above 4 to 5 MHz, such as 40m signals at 7MHz, will not be reflected but will almost completely pass straight through the ionosphere when transmitted directly upwards. Only a very small amount of signal may be reflected back down again as a result of local scattering.

However for those same 40m signals, if we change the angle that the signal enters the ionosphere away from 90°, say to 45°, more of the signal will be refracted back towards the ground again. Another way of putting this is that the Maximum Usable Frequency or MUF for a signal that is refracted from the ionosphere at an angle will be higher than the f0f2 frequency.

A tour of ZL2WT’s Marconi radio room

Here’s a look at one of the most impressive amateur radio stations you’ll ever see: the shack of David ZL2WT.

As David explains:

As a young man, I had a career as a Radio Officer with the British Royal Fleet Auxiliary. On these ships we had a naval radio room, where messages to the fleet were received by teleprinter. There was also an adjoining commercial radio room, typical of what was found on a merchant ship. From here, communication was achieved solely by Morse Code.

Since the discovery of radio, ships would communicate with coast radio stations and other ships using Morse Code. In the 1990s, however, maritime satellite digital communication became established and wireless telegraphy equipment was removed from all ships. The maritime radio frequency bands, which used to resonate with the sounds of dits and dahs, are now silent.

At about that time, when the radio equipment was being removed from ships, I rescued some of the equipment and set up a recreation of a ship’s radio room at my home.

SKN this weekend

SKN this weekend

One last reminder: Straight Key Night is this Sunday from 8 to 9pm on 80 metres. Don’t forget the new QSY Rule!

Full details at zl1.nz/skn

More comments on the Lightning bug

Bob ZL1AYN follows up on an article from our most recent newsletter:

I can echo your comment about Bruce ZL1BWG’s bug having a lowest speed of 30wpm from practical experience.

In 1966 I served in the army at Papakura Camp and it was one of my duties as the Communications Troop Sergeant to instruct unit radio operators from scratch. We used Morse on low-powered HF radio over considerable distances, so the guys had to be accurate and competent in all aspects of communications.

The unit operators were drawn from a diverse group. Many of them had not used a field radio before. They had to achieve a Morse speed of 15wpm as well as learning voice procedures, antenna theory and all the other Q and Z codes and morse procedures for use when out on patrol.

The British Army training manual states that 15 forty minute periods of morse training was the average time for each 1 wpm increase in speed. We used to do it in 10.

Our unit did not have a tape library and it fell to me to send every morse training run by hand, which was a real chore and I used to get to the stage at the end of the day where I had real difficulty in sending characters with more than three dits in them.

So I saved up and bought my first bug for US$54, a considerable sum of money in those days. But, the first time I sent the figure 5, the trainees almost ran out of the room in despair – and so did I. I made contact with Vibroplex and got another weight sent over, which tamed the monster and I could set the key up for 15 wpm characters.

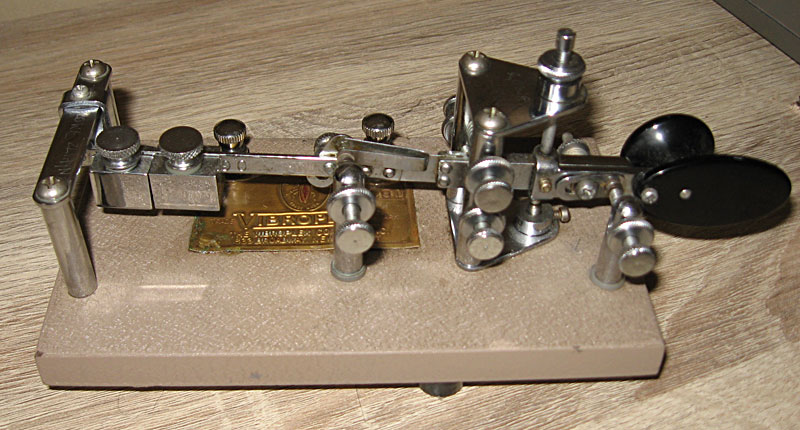

ZL1AYN’s Lightning bug (c1972) with two weights

I liked the bug, because once I had settled it down I could use all manual on one side or give it heaps in full mode. If I need to go into contest mode I only have to move one or both of the weights along the bar and get 30+ wpm.

So as you say in your item “Of course, these bugs can be slowed down with a little extra weight on the pendulum (thank goodness).” I echo that (Thank Goodness).

– Bob

Thanks for the great story Bob. I’ve heard of a few tricks to slow down a Lightning bug. Because it uses a flat pendulum, and a square weight, it’s fairly easy to add some mass to the pendulum. Some ops use a brass stair gauge, such as shown here, as these are readily available from hardware stores.

Thanks for the great story Bob. I’ve heard of a few tricks to slow down a Lightning bug. Because it uses a flat pendulum, and a square weight, it’s fairly easy to add some mass to the pendulum. Some ops use a brass stair gauge, such as shown here, as these are readily available from hardware stores.

Another approach is to extend the pendulum, with a weight attached outboard of the damper.

A quick way to check your Morse speed

A quick way to check your Morse speed

Many years ago, Gary Bold ZL1AN mentioned this useful trick in one of his Morseman columns in Break-In:

Send a string of dashes for 5 seconds. The number of dashes you sent is very close to your speed in words per minute.

Net tip

This relates to checking into the Net using your sine (abbreviated callsign).

If you check in with your sine, and NCS repeats your sine, then you know that NCS is ready for your check-in.

Proceed to send your full callsign, your signal report and your traffic (either QRU or QTC).

You do not need to pause after sending your full callsign to be acknowledged a second time by NCS. When you hear your sine sent back to you, you’re in!

Example:

NCS: QNI PSE ZL1NZ: Z NCS: Z ZL1NZ: DE ZL1NZ GE DAVE 5NN QTC1 ZL4KX NCS: ZL1NZ GE NEIL 5NN <AS>

Suggestions?

If you have suggestions on how to make the NZ Net better, or things you’d like to see covered in these updates, please contact ZL1NZ. You might even like to write something for the newsletter.

Thanks for reading, and I hope to see you soon on the NZ Net!

—

Neil Sanderson ZL1NZ, Net Manager

New Zealand Net (NZ NET)

3535.0 kHz at 9pm NZT Mon-Fri