This is a fortnightly newsletter about the New Zealand Net. If you would like to be notified by email when a new edition is published, please contact ZL1NZ.

Browse our newsletter archive.

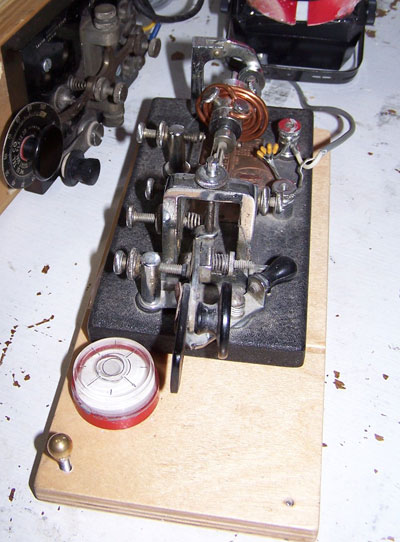

Featured key

The Kent Single Paddle Key is a simple and attractive key that features lots of flexibility in adjustment, as explained by Kent Engineers:

“This is achieved partly by our own spring arrangement, which allows independent left and right spring tensions with finger tip adjustment. Also, the use of precision-made contact screws with instrument knurled heads and locking nuts to allow for precise and positive gap setting. The smooth operation of the key is due to the high quality shielded ball race bearing, not found in any other key of this type. All machined parts are manufactured by ourselves from solid brass and mounted on a powder coated heavy steel base for stability.”

This key is available assembled (€111.30) or in kit form (€98.90), the kit taking less than an hour to assemble.

BONUS: See the video below for tips on making this key even better.

* If you have an interesting key for this feature, please send me a nice clear photo and a few words describing it.

Quick notes

Will there be a 2021 Field Day? At this point, it looks like the Covid-19 situation in New Zealand will allow this annual radio tradition to take place next weekend. Let’s hope so. If you do manage to participate, would you please try to get some good photos of your CW operators at work, so that we can feature them in the next newsletter? Thanks!

The 500th session of the NZ Net was on Friday 19 February. Thank you everyone for helping make the Net a success.

Gerard ZL2GVA filled in as Net Control Station for four evenings while Grant ZL2GD was holidaying at Pohara Beach (and doing the occasional QNI from his portable station). Thanks Gerard.

On 15 Feb the Net was conducted on 3537kHz due to the earthquake the previous day in Japan. The Japanese Amateur Radio League’s band plan lists 3535kHz as an emergency frequency, so we avoided it as a courtesy, although no Japanese stations were heard on that frequency at Net time.

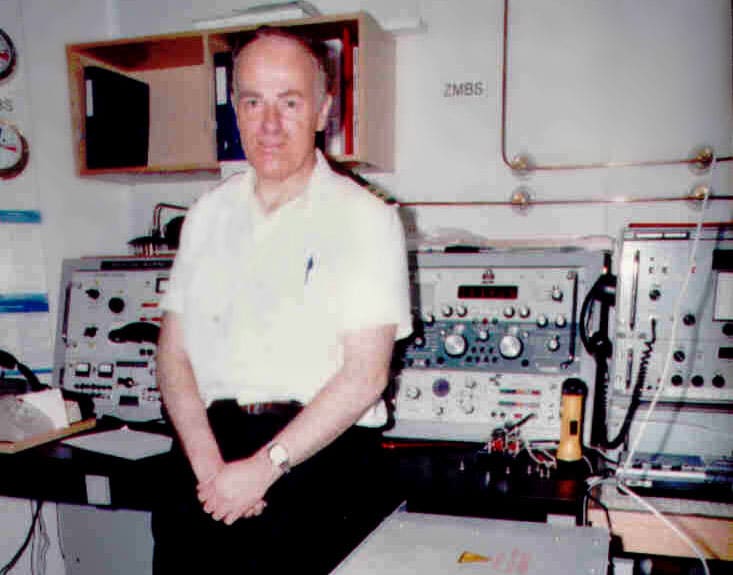

Photo flashback

David Hopgood, Radio Officer aboard the inter-island ferry Arahura in the 1980s

Our flashback photo has special significance. It was 35 years ago, on 16 February 1986, that a New Zealand pilot ran the Soviet cruise ship Mikhail Lermontov UQTT onto rocks in the Marlborough Sounds. As most of our readers will know, the ship sank with the loss of one crewmember, and there has never been a satisfactory explanation for the pilot’s actions, or many other strange things that happened on that day. David ZL2WT has written a fascinating account of the loss of Mikhail Lermontov with exmphasis on the radio communications, which were just as mysterious as the actions of the pilot.

Getting back to our photo: David Hopgood was Radio Officer aboard the inter-island ferry Arahura ZMBS when it picked up survivors from the shipwreck. He told me that as Arahura headed for Wellington with crew and passengers from Mikhail Lermontov, they had to keep the cruise ship’s captain and the New Zealand pilot well separated – because the Russian was ready to kill the man who sank his ship.

Morse musing: learning the code

Our series continues, this time with Stan ZL3TK recalling how he learned the Code. We’ll have more in future editions, but if you haven’t sent me your story yet, please do!

The year is 1960 and there is a radio club at Mt Albert Grammar School in Auckland which has been allocated amateur call sign ZL1ACU. It has a patron, trustee Ivan Gee ZL1AQO, AREC section leader at Western Suburbs Radio Club. It is housed in a disused concrete-lined film projection box behind the ‘gods’ at the back of the assembly hall. On the operating bench is a rather nice R1155 receiver, accompanied by a 15W AM transmitter with an 807 final, home-brewed by the science master of the day, Laurie Woolloxall, also a ham. A half-wave 80m delta-fed antenna is stretched across a wide courtyard between two high gable-ends of the main school buildings, with 600 ohm, open-wire feeders passing through a high-up window frame, then draped above the heads of those gathered in the hall till they reach the old projection box. The members of the school-boy radio club are on the air using a carbon microphone housed in a ping-pong bat-shaped black Bakelite handset with a press-to-talk switch on the side. One day a Morse key arrives unannounced on the operating bench, but no one knows what to do with it so it doesn’t get used.

Gulbransen receiver. Photo: vintageradio.co.nz

Not long after I started work at Automatic Telephone & Electric Company, a colleague from California was about to depart the country and wanted to sell a radio receiver that he’d brought with him from the USA. I asked him about the radio and he invited me to visit his apartment to see if I liked it enough to buy it. It turned out to be an eight octal-valve Hallicrafters S-85, and to me it looked, and smelled, smashing. A generous layer of house dust warmed by hot valves gives off a unique ambience!

He wanted £15 for it – nearly five weeks wages after tax and paying board. I was dubious, but the BFO sealed the deal. Still curious about the whispering effect we’d heard on the Gulbransen, I was tuning around 3.3 Mc/s using the band-spread dial and found it again. My American friend, who apparently knew more than he was letting on, reached over and flicked on the BFO switch.

Wow! It all came to life, no more ‘whispering’. Instead there were strings of clear dots and dashes. That was the first time I’d heard Morse code as tones, and that’s also how I became a ‘mortgagor’ for the first time, not to own land, but to finance the purchase of that receiver. My aging Edwardian adoptive parents were horrified by what they believed was a naive decision, and somewhat bemused as to why their varnished wood-veneer Gulbransen was not good enough.

Wow! It all came to life, no more ‘whispering’. Instead there were strings of clear dots and dashes. That was the first time I’d heard Morse code as tones, and that’s also how I became a ‘mortgagor’ for the first time, not to own land, but to finance the purchase of that receiver. My aging Edwardian adoptive parents were horrified by what they believed was a naive decision, and somewhat bemused as to why their varnished wood-veneer Gulbransen was not good enough.

It turned out that the Morse on 3.3 Mc/s was coming from ZKF, a station at Ohakea Air Force Base in the Manawatu. ZKF was used for training radio operators in all three armed services. From memory it began transmissions every week night with military precision at 1830 hours, transmitting at 5 wpm, the speed incrementing by 5 wpm every 15 minutes until it ended at 2000 hours at 30 wpm. The text consisted of war stories, just like those I’d found in the eclectic array of books my father had bought during and immediately after the war, and stored behind the closed doors of an ancient, dark-vanished, borer-ridden bookcase in the lounge room.

The Morse transmitted by ZKF had a near perfect mark-space ratio controlled by punched paper tape. There was no Koch or Farnsworth in those days to speed up the learning process, so the only way to learn Morse was to plunge in at the deep end. It took a good couple of months of dedicated effort after work, night-after-night, listening to ZKF on my Hallicrafters and writing the text down in cursive script, before I could pass the 5 wpm NZPO test for a Grade 2 license.

That turned out to have been the easy part. It took slightly longer than the full, mandated year, as well as experiencing plenty of soul-destroying plateaux, before I had gained sufficient confidence at 20 wpm to sit the Grade 1 exam at 15 wpm. That’s how it was done in those days. Just 15 years after William Shockley Jr had invented the bipolar transistor, one learned CW without a computer in sight.

How did you learn CW? Drop me a line and I’ll post the replies in future newsletters.

Video: Improving the Kent Single Paddle Key

Sadly, 2B Radio Parts, mentioned in the video, is no longer in business.

Field Day idea

Field Day idea

“I like to use my old bug at Field Day but the tables are never flat, nor are they level. So, I mount my bug on a pine board with a bubble level and a three-legged support with one leg being a screw-adjustment to make the bug level on any convoluted table-top.”

– Glen Ellis K4KKQ

Editor’s note: Glen appears to have slowed down his bug with some heavy-gauge wire wrapped around the weights. He has also mounted a straight key to use horizontally.

Net tip: Correcting errors, the correct way

Most of us make the occasional mistake when sending Morse. In casual ragchewing, we might figure that an error wasn’t very serious, or that the other op can easily understand what we meant, so we sometimes decide to just carry on without correcting the error.

But there are times when it is essential that we inform the other op that we’ve made a mistake and are going to send a correction. This is certainly the case when traffic-handling, as only perfect copy is “good enough.”

![]() The Morse signal for “correction” is eight dits, sent as a single character, and often written as <EEEEEEEE>, although I prefer to write it as <HH> because I’m lazy.

The Morse signal for “correction” is eight dits, sent as a single character, and often written as <EEEEEEEE>, although I prefer to write it as <HH> because I’m lazy.

But eight dits can be a challenge to send. It seems harder to commit the sound of eight dits to memory, in the way we remember shorter sets of dits, such as S, H and 5.

![]() So, in practice, “approximately eight dits” will do the job. And they don’t even have to be run together as in <HH>. They can also be sent with spaces, e.g. E E E E E E E E.

So, in practice, “approximately eight dits” will do the job. And they don’t even have to be run together as in <HH>. They can also be sent with spaces, e.g. E E E E E E E E.

![]() Sometimes we hear ops using <IMI> (“I repeat”) instead of the correction signal – but I feel that this is bad practice and potentially very confusing.

Sometimes we hear ops using <IMI> (“I repeat”) instead of the correction signal – but I feel that this is bad practice and potentially very confusing.

Consider these situations:

A station sends the preamble of a radiogram and, when they get to the Check numbers, they send this:

25/23 <IMI> 25/23

The meaning of this is clear. The check is 25/23, and just to make sure we got it, the op has repeated it.

But what if the op makes a mistake and uses <IMI> instead of the proper correction signal?

25/22 <IMI> 25/23

Now, the receiving op will be bewildered. The two checks should be identical, since the second is supposedly a repeat of the first. But they’re not the same, and we can’t assume the second one is the correct version.

The sending op should instead send this:

25/22 <HH> 25/23

They might even send the correct check numbers twice, for reassurance:

25/22 <HH> 25/23 IMI> 25/23

Nobody should be embarrassed about using the correction signal. Just like asking for fills, it shows that we care enough to make sure our communication is 100% clear.

Advertising archive

Introducing a new series in NZ Net News

SX-71 receiver in a Hallicrafters advertisement, 1954

Suggestions?

If you have suggestions on how to make the NZ Net better, or things you’d like to see covered in these updates, please contact ZL1NZ. You might even like to write something for the newsletter.

Thanks for reading, and I hope to see you soon on the NZ Net!

—

Neil Sanderson ZL1NZ, Net Manager

New Zealand Net (NZ NET)

3535.0 kHz at 9pm NZT Mon-Fri